Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) attempts to determine the economic value a customer brings over their “lifetime” with the business. At the heart of understanding CLV lies the recognition that a customer does not represent a single transaction but a relationship that is far more valuable than any one-time exchange.

However, CLV is not about any one customer; it is about stepping back and taking a look at your customer base as a whole — understanding that while some never return and some never leave, on average there is a typical customer lifetime and that lifetime has a specific economic value.

Understanding Customer Lifetime Value is incredibly important for customer service professionals and for businesses of all types. Why?

Because if you don’t know what a client is worth, you don’t know what you should spend to get one or what you should spend to keep one.

For instance, if it costs you $100 to acquire a customer, and your customer’s CLV is $75, then we’ve got a problem Houston.

Understanding CLV allows you to drill down and understand the economic value of each customer, so you can make sound decisions about how much to invest in acquisition and retention.

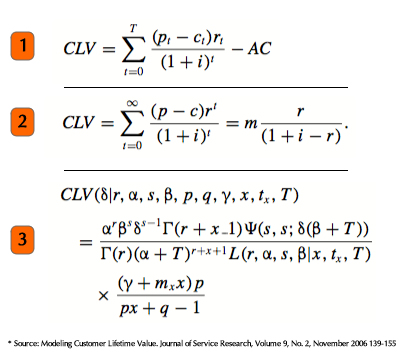

The Customer Lifetime Value calculation can be an extremely complex undertaking. Both correctly identifying the underlying components and calculating the end result have been the focus of numerous academic studies. To say that it can be complicated would be an understatement. Here are three examples of CLV calculations from the academic literature.

While anyone with a graduate course in finance or statistics can probably hack their way through the first two formulas, the third looks like something pulled off one of the whiteboards from the set of The Big Bang Theory. I’ve been exposed to some fairly daunting business math in my day, and if I had been shown the last formula out of context I wouldn’t have known if it was designed to calculate Customer Lifetime Value or the quantization of energy.

So, if calculating Customer Lifetime Value is so mathematically challenging, do we have to go full geek to effectively use CLV in our businesses?

The answer is no.

While it is wise to be cautious about using nonscientific evidence for analysis, often statistically sound approaches are not feasible. Whether due to budgetary, time, or data constraints, sometimes the back of the napkin is all we have.

Yet sometimes the back of the napkin is good enough. When people apply common sense and experience to non-scientific evidence, the process can often yield extremely positive results.

Much of the reason for this non-geek guide to Customer Lifetime Value is the understanding that, even if you don’t whip out the slide rules and try to create a scientifically sound model, spending time on each component of the CLV model can be incredibly instructive.

Whether you are measuring the value of customers in your department, your small business, or even your blog, just thinking about CLV and its parts can help you refine your marketing and retention efforts.

Let’s begin by taking a look at the major components of Customer Lifetime Value.

The tendency when thinking about the lifetime value of a customer is to focus on the revenue the customer brings in over their lifetime. However, focusing on revenue will almost always overstate the value of the customer. The more accurate way to measure is to focus on what is known as the Unit Contribution Margin, which we’ll call marginal profit for short.

Calculating marginal profit is simple in many industries. For instance, if a Starbucks customer buys a $5.00 latte, that transaction has costs associated with it. The milk, the cup, the coffee, the lid, and the flavoring all add to a variable cost that is incurred for that latte transaction.

Let’s assume those costs are $1.50. It’s obvious that if you wanted to calculate the Customer Lifetime Value of a Starbucks customer, you would want to use the $3.50 of marginal profit as your metric, not the $5.00 of revenue. Using revenue overstates what you made on the transaction. The true economic value of the transaction is $3.50.

The next step is figuring out the average of all of the company’s transactions. Not everyone buys the $5.00 latte. Some buy the $3.00 muffin, others buy the $1.50 straight coffee. The trick for Starbucks is figuring out how many of each and calculating an average profit profile per customer.

In the end, Starbucks would hopefully come up with something like: the average Starbucks customer spends $4.30 at an average cost per transaction of $1.10 — thus the marginal profit for an average transaction is $3.20. (PS. All of these numbers are hypothetical.)

It is important to note that in this case, labor is not a variable cost. Ignoring anomalies like sending staff home on a slow day, Starbucks’ labor is constant. They are paying the staff whether that cup of coffee is purchased or not. Thus, it does not contribute to marginal profit.

Labor would be included, however, if labor costs vary based on whether a service is performed or a product is sold. For instance, maid services that pay only per job or spas that pay per service performed. Product companies can also have variable “labor” per unit, if for instance, there are commissions paid on sales.

But I work for myself…

For consultants or solopreneurs, the calculation can be tricky. If your hourly rate is $50 and you provide 10 hours of service, $500 will be your revenue, and $500 will be your cost. How do you value the cost of your time compared to your hourly rate? My suggestion is to use opportunity cost.

The presumption is that you charge a different hourly rate yourself than you would presumably receive as an employee. Calculate what hourly rate you would be earning in an alternative employment situation and use that opportunity cost as the cost of your time. If you made $20/hour at your last job or you think that’s about what you would get if you sought employment, then use that number as your cost.

Since your primary cost is the value of your time, you have to determine the opportunity cost of taking that hour away from other economic alternatives and spending it on that client. It might be a wild guess, but it can still be instructive.

To understand CLV, you must know the lifetime of your customer. Now, we will have to do a little math here, but it is just dividing a couple of numbers, so it still qualifies as non-geek.

Calculating customer lifetime can actually be fairly simple if you have the data. The first step is to calculate your customer retention rate, and then do some simple division to get your customer lifetime.

To calculate your retention rate, take the number of customers from last year who are still customers this year — that is your retention rate. If you had 100 customers last year and 45 are still doing business with you this year, then your retention rate is 45%. (For a more sound approach, you would want to track it over multiple years and take an average.)

Once you have the retention rate (RR), then it is easy to determine customer lifetime. Simply apply this formula:

CL = 1/(1-RR)

In this case, CL = 1/(1 – .45) = 1.8 | Your customer lifetime is 1.8 years.

An important consideration is whether your business has time-bound contracts with customers. Mobile phone providers and fitness clubs will have different characteristics to consider when approaching this metric than businesses that don’t have contract periods as part of their customer relationship.

In non-geek, the discount rate is the interest rate you borrow money at in your business, and it is essential to knowing the true value of your customer’s future cash flows. The concept is based on the time value of money, the premise that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow.

If the lifetime value of a customer is fairly short, the calculation, while methodologically sound, might not be material. However, if you have a long time horizon, the time value of money is a real consideration. To put it in perspective, would you rather have a $100 from your customer today or twenty years from now? Of course, we all know the answer to that. 20 years from now you’ll be lucky if $100 buys you a ream of paper for your copier. (As if we’ll be buying paper for copiers in twenty years!)

For our back of the napkin purposes, you are probably safe to ignore the discount rate in calculating your Customer Lifetime Value. Just understand that the longer you calculate your customer lifetime to be, the more important the discount rate becomes and the more inaccurate your model becomes when you ignore the rate.

At the heart of customer segmentation is the belief that all customers are not created equal and that understanding the differences among customer segments is key to effectively acquiring and retaining customers.

Depending on the nature of the business, customer segmentation can require some serious mathematical analysis to be done properly. However, in the spirit of our non-geek guide, we will approach customer segmentation by asking one simple question:

How would I group my customers if I wanted to customize my marketing, retention, or product offerings?

Customer segmentation can occur on many bases: demographic, psychographic, behavioral, and so forth. The key is knowing which breakdown is most valuable for your business.

The most logical first step is to break down the segments based on differentiated products or services. For instance, say your department provides support services both to small businesses and individuals. If the offerings to these two types of customers are distinct, you would probably want to segment your customer base into business customers and individual customers. In other words, you would calculate a Customer Lifetime Value for each segment.

If your business does not have obvious divisions like the one above, you should consider what factors have the most impact on customer buying characteristics — or segment on behavior itself. In the first case, you would simply ask yourself what impacts purchasing. Do men and women have different buying patterns? Is household income important to purchasing behavior? Is there a psychographic factor like “plays golf more than twice a week” that really differentiates activity?

Sometimes behavioral data, how the customer behaves with your business, is the best way to segment. Do you retain customers who buy your premium product at a significantly greater rate than all others? Is three purchases the magic number that makes a customer stick significantly longer? Do customers who remain after 9 months increase their average lifetime purchases by more than double?

As you can see, your ability to segment your customer base is directly related to what you know about your customers (or are willing to find out). However, in the spirit of our non-geek approach, let me advise you to start with your gut. If you know your business, you probably have an innate sense of what types of customers act what way. Try to fill in the blanks on this statement:

Customers who ___________ tend to ___________.

For example… Customers who are over 55 tend to retain longer. Customers who subscribe to the newsletter tend to have much higher average purchases.

Go with your instinct first, then dig into your data to try to prove or disprove your hunch.

Technically, the calculation of Customer Lifetime Value should include acquisition and retentions costs. To know a customer’s true lifetime value, you need to subtract the cost to acquire and keep that customer. However, I find it helpful to calculate CLV without acquisition and retention costs. To me, this is the best way to isolate variables and to see their effect when using the back of the napkin approach.

This is similar to the EBITDA concept in accounting — figuring out your earnings before taxes, depreciation, and amortization. It gives you a sense of the purely operational figure, outside of the other inputs.

Let’s start with acquisition…

Knowing what it costs to get a customer in the door is one of the most valuable pieces of information any business owner can have. Customer acquisition costs are generally the easiest of the metrics to compute. While each industry and business is different, the broad brush approach is simply to take your marketing expenditures for a period and divide by the number of new clients in the same period.

Try to find a period that is relevant for your business based on how you approach your marketing, and how much lag time there is in your business between marketing and acquisition. Don’t forget hidden marketing costs such as loyalty or customer referral programs.

If you are a small business / solopreneur, you would need to measure time spent on blogging, social media, or content creation. If your web site and social media are your only sources of new customers, you would take the time spent on these items in a month, multiply it by your hourly rate, and calculate your marketing cost.

Whatever method is appropriate for your business or department, the goal is to figure out exactly what it costs to acquire a customer.

If a customer stays with you, on average, for 2.5 years, what are you spending to keep them coming back? Most companies put money into retaining customers, and much of the focus of customer service and customer experience writing is about the retention of customers already acquired. Calculating these costs can be a challenge, because there is a much greater mixture of hard costs and soft costs in this area than are found in the marketing bucket.

Start with any obvious hard costs: perks for longevity, discounts for existing customer, freebies for certain buying behaviors, etc. These are the costs that can usually be calculated easily and accurately. When making the calculation though make sure to average the cost out across the entire customer base.

In other words, if you gave $1,000 in longevity discounts last month, but only 25 of your 5,000 customers received the discount, you would still spread that cost across your entire database of 5,000, not just the 25 who received the discounts.

Soft costs are trickier. If you add a part-time person so that your manager can focus on customer outreach, is that a retention cost? If you send your sales staff to a customer service seminar, is that a retention cost? If you redesign the help section on your web site, is that a retention cost? While it can be difficult to determine how to treat soft costs when looking at retention, it is well worth the time to evaluate.

One question that should help determine if a soft cost belongs in the retention “bucket” is this: what is our primary reason for incurring these costs? If customer satisfaction, retention or any similar customer service-based sentiment is the primary reason, it is probably safe to consider the expenditure a retention cost.

A final note on acquisition and retention: If you are segmenting your customer base, you will need to apply these calculations for each segment, not the customer base as a whole. In fact, these acquisition and retention analyses truly show their power when applied to meaningful customer segments, as you will see when we begin…

Now that you have your CLV and a grasp on your marketing and retention costs, it is time to start putting the two together. Even when taking the scientific approach (which we are not), this part of the process can involve a good bit more art than science. A few extremely hypothetical (and yes, very simplistic) examples will hopefully get the wheels spinning on how to approach this final phase in your specific situation.

While we are only going to break down acquisition and retention, there is a third strategy that is important to bear in mind: customer expansion. Instead of purging customers with low or negative CLVs, you attempt to expand your business with them and help them become more valuable customers.

A suburban golf pro shop determined that their customer base broke down quite naturally by geography. The pro shop determined that most of their customers came from two zip codes, one to the east and one to the west, and accordingly, the pro shop decided to calculate the CLV separately for each zip code. What they discovered was that the CLV for the east customers was 4 times the CLV for the west customers.

Once they dug into their stats, they found out how important this differentiation was. The east zip was 30% of their customer base but 80% of their profit. The west zip represented 70% of their customer base and 20% of their profit.

The pro shop had been spending their marketing dollars evenly east and west. Even though they knew the customers from the east were more valuable, they continued to put 50% towards the west because it seemed more effective. They were simply getting a much better “response” from the west marketing. Calculating the CLV for each segment made it obvious that the marketing dollars were not being allocated effectively.

A chiropractor instituted a Chiro-Bucks rewards program to help retain patients. Patients could earn points for various activities, from receiving services, filing their own insurance, or referring other patients. These points translated into straight dollars off. After a year using the points program, the chiropractor found that it was being used heavily and, when averaged out among his entire customer base, represented almost 10% of CLV.

Unfortunately, the increase in retention since starting the program (other factors assumed constant) had only been 2-3%. What the chiropractor found is that Chiro-Bucks had not extended the life of the majority of customers; most tend to use chiropractic until they no longer need it or insurance no longer covers it. The Chiro-Bucks had simply helped keep some people that previously would have defected to another chiropractor due to dissatisfaction with the service, the majority of whom could probably be saved by implementing better service systems. Understanding CLV had enabled this chiropractor to see that the Chiro-Bucks program had a cost far greater than its long-term economic value.

Of all the many exercises in a business, computing Customer Lifetime Value can be one of the most eye-opening and rewarding. Hopefully, the point has been well-made by now that knowing the lifetime value of your customers can help you truly understand the value of your marketing and retention expenditures.

The goal of this post was to provide a detailed look at a broad brush approach to CLV — to address how to think about Customer Lifetime Value as much as how to calculate it.

What should you takeaway from this post? Hopefully, that you can derive true value from a back of the napkin approach to CLV, but that you should realize the limitations of using such a non-scientific approach. Each business is different, but there might be a time where you feel the need to get your geek on. If so, below are some resources for further exploration of Customer Lifetime Value.

Comments are closed.

© 2011-2025 CTS Service Solutions, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Legal Information | Privacy Policy

How to Cite this Site

We know this very well, especially with commercial insurance because we are seeking long term relationships. The new sales are the lifeblood for growth and expansion, but it is the current customers who pay the bills. We probably lose money the first year on most new relationships because of all that goes into acquiring a new customer. However, because the majority of our relationships are 5-7 yrs +, it’s year 3 through 7 where it really pays off.

The moral of the story is, know your target audience just don’t chase every cat and dog out there, and take care of the ones you have.

We break our measurement down to revenue per employee from an agency perspective. Right now our revenue per employee is about $130,000 per; that benchmarks well with our peers. To increase that, we have to target larger accounts, but that seems to be where our sweet spot is.

The other key is don’t get bogged down in non-profitable accounts at the expense of the true revenue drivers. There is a hierarchy and the 20/80 rule applies; make sure you take care of the ones driving the train, right?

Good post and very appropriate for my industry.

Insurance is a great industry for tracking these metrics and using them to make decisions. You know exactly who your customers are, how much they spend with you, how long they’ve been with you, etc. Thanks so much for the real world example — that’s exactly the type of thing breaking down the customer patterns can really tell you — that customers are not that profitable the first two years, are most profitable from 3-7 years, etc. Also, as you point out, looking at the 80/20 to find the ones that are not helping move the train forward.

Awesome comment Bill! Thanks for taking the time.

Adam, thanks so much for putting this amazing blog together. It’s such a great roadmap for having us all think about CLV and all of the potential variables. As you said, this information most likely needs to be absorbed over time, but each of your points are excellent and thought-provoking. This must have taken you a long time to create, but it’s definitely worth a great deal to your readers. Richard Shapiro, The Center For Client Retention @richardRshapiro

I really appreciate that Richard! I’m glad you found the post useful — and yeah, this one took some time! 🙂

Thanks so much for your comment. It’s great feedback to get from someone with such deep experience in client retention!

One of the reasons I got out of being a satellite retailer with Dish Network and DirecTV was that they would frontload the commissions on the customer, but cut out a lot of the long term value with reduced residuals. There are side things you can do like Home Theater, Audio, and things of that nature. However, I used some formulas similar to the above, and decided to move on after a strong analysis. It’s much better to have a business where you can do business with your customer much more than once in my opinion.

Interesting. I don’t know much about satellite system sales, but if I understand what you’re saying, it was setup so that the CLV was profitable for the company, not you as a salesperson. That’s an interesting perspective on CLV I didn’t delve into here.

I like how you used sort of a “personal CLV” to determine whether the position was right for you. That’s awesome!

Thanks for sharing your story Jon!

This is a common strategy used by merchants and drawback for affiliate marketers. Many merchants take the position that once a customer buys anything they are now “their” customer and want to eliminate payments for any subsequent purchases referred by the affiliate.

This is short-sighted because if the additional sales were driven by the affiliate the customer is actually still the affiliate’s and the merchant has not converted that customer to their own processes. The affiliate is in fact responsible for any subsequent sales they refer because they sent the buyer back.

To put this another way, even if a merchant has a mailing list and even if the repeat buyer is on that list, if they are coming back to buy through a link on that other person’s site the other site IS responsible for generating that sale.

Hi Gail,

You make a great point. I would add slightly on one point. I think a lot depends on the industry norms and most importantly, what the company states they are willing to give up front (in other words full transparency). In the end referral bonuses or affiliate commissions are a marketing cost, and a company should have the right to say what they are willing to give to obtain a customer — and that might not be continuing residuals.

As I mentioned, the industry is also important. If a store offers, “bring in a friend a get a free ice cream” no one really expects that the referring person will get a free ice cream every time the friend comes back. With online affiliate commissions, the expectations for residuals deeper in the relationship are higher.

As we know, there are many companies who do not run transparent affiliate programs. I think as long as a company is up front with the affiliates from the beginning about what and how they pay, then affiliates can make their own decision about whether referring their company is worth the time and effort. Just like Jon did with his satellite gig.

Like any good business relationship, the most successful ones are where both parties win!

Thanks for the great comment Gail! Much appreciated.

Pingback: Monthly Mash: Customer Experience Tools and The HootSuite Owl

Hi Adam,

Well I always find these business terms always difficult to understand. But I do want to ask you one thing that if I have 8 customers 6 of comes twice in a week and makes purchase of $10-20 and 2 of them comes once in a month and make purchase of $200, then who have more customer lifetime value. The 6 who comes frequently but makes less or those who come rarely but make greater purchase.

Regards.

Pingback: How This Blog Will Change in 2012

Pingback: Guarantees and Prompt Refunds - Best Business Practices, Good Customer Service (Does Your Refund Policy Suck?)

Hi Adam,

Thanks for this.

Customer lifetime value is the key to effective paid advertisement. When the CLV is huge, then it would make sense to spend a percentage of it via a leadloss sale to acquire a customer.

Dating industry is one of those industries that have very high CLV.

It is very common to find a dating site giving 200% commissions to their affiliates.

Hi Jeff,

Thanks for the comment. And you’re right, that’s one of the reasons knowing the CLV is so important, knowing what you can pay for acquisition. Interesting stat on the dating sites. Thanks for stopping by!

I loved that picture from the Big bang theory! Oh sheldon.

Thanks for the great post, very useful in training better customer service.

I’m glad you liked it Chris.

Hi Adam

I’m doing this project for my Master and it’s about CLV. My company for this is Starbucks. I am using the Reinartz & Kumar, 2003 model and I can’t find some values for the variabes: Acquisition Cost (for a customer) and for Direct Cost of Servicing the Customer (this can be in weeks, months or years).

Do you think you can help me with some approximate values?

It would really help me a lot…

Thank you,

Florin

Hi Florin,

Thank you for your questions. I’m not sure if you noticed in the post, but the numbers I used for Starbucks were hypothetical. I do not have access to Starbucks’ actual acquisition costs and direct cost of servicing. You can check out the infographic in this link (and its sources): http://blog.kissmetrics.com/how-to-calculate-lifetime-value/ This uses actual data from Starbucks; however, it is from 2004, so I am not sure if that is recent enough for you.

If not, my recommendation would be to contact public relations or community relations at Starbucks. Oftentimes, companies will help students with non-sensitive information, though that is not as common as it used to be.

Hope this helps. Best of luck with your project and your degree!

Pingback: What Is a Customer Worth? Customer Lifetime Value via SlideShare

Hi Adam,

thanks so much for this fantastic article.

i will translate part of it to Persian language for our website audience and students here :

CLV is the key to effective customer service.

Thanks for sharing.

best

Thank you for the kind words. Glad you found the post useful.

Pingback: Customer Lifetime Value Explained

Pingback: What Is an Internal Customer?

Pingback: 5 Principles for Great Restaurant Customer Service

Pingback: Customer vs. Client: Is There A Difference?

Pingback: The Ritz-Carlton’s Famous $2,000 Rule

Pingback: Monthly Mash: Customer Experience Tools and The HootSuite Owl

Pingback: How to Destroy a Customer Relationship in the Final Moments