I had an extremely disappointing experience with my car company the other day. Though I have every right to call this company out, I am not going to say who the car company is.

Instead, I would like to focus on what happened and how a company can do extreme damage to its brand and to customer loyalty by using bait and switch marketing tactics.

I have owned the same car for six years. I’m a drive ‘em ’til they drop kind of guy. The brand I own is known for its longevity, and my plan was to drive the car for at least another four years — until it turned 10.

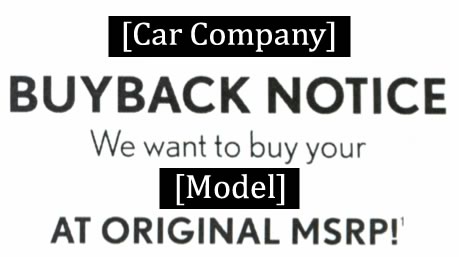

However, a few weeks ago I received an offer from my car company in the mail. The offer was astounding — it offered me the chance to trade in my 6 year old car for the original MSRP!

Now, I’m no Good Will Hunting in the math department, but it did not take me long to realize what my car company’s offer meant. Essentially, I would have had driven my car for the past few years for the cost of the payment interest and maintenance/repairs. Not too shabby.

And also, not too realistic.

The basic economics did not make sense to me, so I was skeptical. But I also did not shut the door — perhaps there was some government program or corporate tax rebate that made the offer economically viable? What could it hurt to ask?

I quickly skimmed the entire page and did not see a catch, and I even glanced at the first few sentences of the fine print.

As I said, I was not in the market for a new car, but I had a service appointment coming up, so I figured I would just ask about the offer while I was at already at the dealership.

As always, I had a good experience dropping my car off at maintenance. Once inside the dealership, I was directed to a gentleman, whom we’ll call James, who was wearing a coat that had a monogram touting the new buyback program.

“James,” I said. “Angela told me I should speak to you about the buyback program.” I showed him the letter I had received from the dealership. His first words were not how are you and were not I’d be happy to tell you about it. His first words were…

“I need to let you know that we will not give you MSRP for your car.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“We take the original MSRP but then we take off for depreciation, like time, wear and tear, and miles driven.”

“So basically, you value it just like you normally value a used car.”

“Yes,” he replied, and I could tell this conversation was not a new one to him.

I pointed to the big MSRP call out (pictured above). “I have to say James, that’s just outright deceptive.”

James apologized, and I walked back to the lounge to wait for my car.

But none of this was James’ fault. In fact, you can tell he and his teammates had been getting hammered by customers about this shady offer — why else would he start his sales pitch with “I need to let you know that we will not give you MSRP.”

The front line was paying the price for the shady practices of the corporate office.

Fine print is unavoidable. Consumers can scream from the rooftop, and “experts” can tell you how Zappos doesn’t have fine print (they do by the way, but very little) — it will not change the fact that every business has limitations on what it can do or will do based on the economic constraints of its business model.

In today’s hyper-litigious business environment those limitations often have to be protected by legal disclaimers and the dreaded fine print.

However, here is a rule every CEO and CMO should have tattooed to their foreheads:

Fine print should NEVER negate the basic premise of your offer…

…Or the basic premise of your marketing campaign.

…Or the basic premise of your business model.

Fine print is for the exceptions, for the details that qualify the tangential parts of an offer. Fine print should never be used to say “my core message is a lie.”

In customer service, we often have to deal with the impact of fine print on the people it affects. And that is fine; it’s part of the gig. Sometimes you have to have limitations that impact a small portion of your customer base. We handle these cases the best we can.

Fine print, however, should only be used to protect the company, not to take advantage of its customers.

I do not generally get upset by these types of situations, but I have to say that after my interaction with James, I could not wait for my car to be done. I always enjoy going to the dealership. They have Wifi and a great room to work in. It’s a nice change of environment with free drinks and food.

But that morning, I just wanted to get out of there.

I do not know if I will hold this incident against the brand, against the dealership, or just wait to see how the next four years of interactions go. I can say this: the letter they sent me was one of the most blatantly deceptive pieces of marketing I have ever received.

I love my car, and frankly, I probably would not have even looked at another car brand when I was ready to buy again. At minimum, this one letter has taken a loyal customer and prompted him to take a look at the competition. I suspect that plenty of others will not even be that forgiving.

Comments have been closed on this post.

© 2011-2023 CTS Service Solutions, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Legal Information | Privacy Policy

How to Cite this Site

That is terrible! And so short-sighted. Frankly, it sucks that the marketing/advertising department either didn’t do their research to understand the offer (I’m giving them the benefit of the doubt there) or didn’t care enough about the long-term impact on loyal customers and went for the headline that grabs. I hope you emailed them a copy of this post!

Hey Nicole, thanks for sharing! I like to give the benefit of the doubt, but on this one, I’m having trouble doing it. It’s just so blatant; I really wonder how anyone thought this type of thing would fly these days.

As for long-term impact, it was obvious that there had already been so many bad encounters by the time I got into it that the salespeople were throwing the MSRP thing out there up front to avoid worse issues. So I’m guessing there are quite a few upset customers out there.

That’s a terrible trick. A lot of people are not very sophisticated and will be sucked in by that ad (which is probably why they did it). I wonder if that company would like a letter from the FTC.

That’s the sad part Patricia; my guess (I’m not a lawyer) is that the fine print covers the company with the FTC. Yet still, there could be people who fall for it enough to either make a purchase or to at least, as I almost did, have a lot of their time wasted.

I hate when companies do that crap, especially car dealerships. Every time I step foot on a dealership, I swear I go into b—- mode and I don’t really mean too, but they bring out the worst in me. Why? No trust. Sure, they have to make a living too, but you don’t have to rip me off in the process.

That bait and switch thing has happened to me in the past and I just walked out the door with them running after me. I just think back when the economy was really bad and car dealerships were closing up like mad. They would have given you their shirt and pants to make a sale then, but not, its back to the old sleazy tactics to get a sale. No thanks.

I tell you Sonia; I think I’m getting there too. The irony is that this incident is not even close to my worst car buying experience. I haven’t written about the time we bought my wife’s car a few years ago.

The salesperson was so unethical, tried a major trick with the interest rate, which I caught. I had to demand the manager, and then we spent over four hours buying the car, because I read every word on every document and scratched out certain clauses.

We probably should have walked away, but we decided that due to the hassle factor on our side, to just get it done. In the end though, we consider that dealership completely untrustworthy and have never taken the car back there once for service. Also, we will certainly never buy another car from them.

Ah, the dreaded ‘deal breaker.’ In my world when we go to market we might get a proposal but it might include one or two ‘deal breakers.’ No wind coverage, or too high of a wind deductible…..but the price looks really good. A rook or less than credible salesman might not disclose this fact and just hope they don’t have a wind claim. Oh yes, I have seen some do this……..

If you are resorting to trickery and it just doesn’t smell right, then rule of thumb is just don’t do it.

This happened after our lunch? You knew it was going to be a bad day when you had to pay, huh?

Yep, this happened right after our lunch. I should have known…

I would imagine your industry is rife with these issues. As a business owner, who the heck has the time to read every clause in every policy. If you don’t have a trustworthy agent that understands your business, you are in trouble — because you won’t know that you were given a bad deal until you have a claim. And then, it’s too late.

Pingback: Monthly Mash and April Fool's Day